Wc Clifford the Ethics of Belief Contemporary Review 29

The Metaphysical Order was formed in 1869 past a group led initially past the architect Sir James Knowles, the poet laureate Alfred Lord Tennyson, and the astronomer Charles Pritchard. Knowles had a lively involvement in metaphysical exploration and he helped to encourage that taste in his friend Tennyson. Tennyson past 1869 had also been nursing for some time a fear that the Victorian age had become an age of materialism, and consequently inattentive to important spiritual matters. Pritchard, who would presently become the Savilian Professor of Astronomy at ![]() Oxford, was convinced, in the aftermath of the controversy over Essays and Reviews (in 1860), of the need to reconcile scientific knowledge and the Bible and he besides helped encourage the poet'southward involvement in metaphysical speculation (Metcalf 212). Although initially the group wanted to exclude opponents of Christianity from discussions, they shortly became convinced that inviting opponents of Christianity into the Society would guarantee lively discussions of the evidences for Christian belief (Metcalf 214).

Oxford, was convinced, in the aftermath of the controversy over Essays and Reviews (in 1860), of the need to reconcile scientific knowledge and the Bible and he besides helped encourage the poet'southward involvement in metaphysical speculation (Metcalf 212). Although initially the group wanted to exclude opponents of Christianity from discussions, they shortly became convinced that inviting opponents of Christianity into the Society would guarantee lively discussions of the evidences for Christian belief (Metcalf 214).

The Social club ultimately brought together a great diverseness of intellectuals, writers, philosophers, scientists, poets, journal editors, politicians, and Church figures of the era for vigorous debates. The distinguished roster of members included, besides the three most of import founding members, Dean Stanley and Archbishop Manning, the Broad Church theologian F. D. Maurice, intellectuals such as John Ruskin, Leslie Stephen, Marking Pattison, Walter Bagehot, and J. A. Froude, future and electric current prime ministers Arthur Balfour and William Ewart Gladstone, as well as scientists and philosophers such as T. H. Huxley, William Tyndall, Sir John Lubbock, and the immature mathematician William Kingdon Clifford. The group met for nine monthly meetings per twelvemonth from its founding in 1869 until its demise in 1880. At these meetings, papers were read and discussed past the membership and often reprinted in journals such as The Contemporary Review and The Nineteenth Century. The volume Papers Read at the Meetings of the Metaphysical Society contains a consummate roster of the well-known participants (Papers thirteen-xiv).

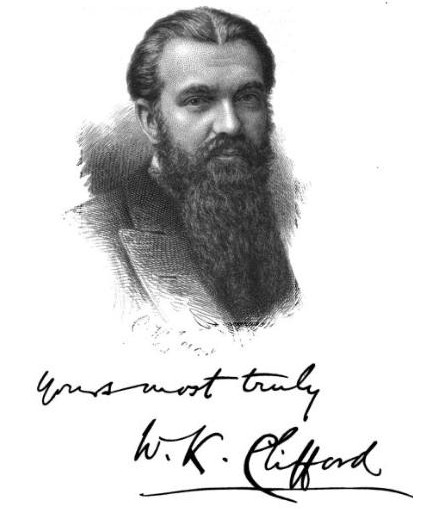

Effigy 1: William Kingdon Clifford, 1901

A brilliant mathematician who taught at ![]() Academy College London, translated the work of the not-Euclidean geometer Riemann, and predictable Einstein's theory attributing the force of "gravity" to an effect of curved infinite rather than the activity of a mysterious strength, William Kingdon Clifford (1845-1879, Fig. 1) was both the youngest member of the "Metaphysicals" when he joined and, eventually, one of the well-nigh provocative spokesmen for the "agnostic" side in the Social club's debates. Clifford was proposed for membership by T. H. Huxley in 1874 shortly after he became Professor of Mathematics at University College London while still in his twenties and he delivered his beginning paper to the group, "On the Nature of Things in Themselves," on the ninth of June, 1874. A strident agnostic, both celebrated and reviled during his brusque life for attempting to ground ideals in the very earthly "conscience of the tribe" rather than orders from heaven, Clifford would draw on the work of Darwin (especially some comments made by Darwin in The Descent of Man [1871]) to redefine the meaning of "piety," associating the term "the pious character" with one who remains faithful to the dictates of the "tribal self," an introjected moral authority whose dictates serve a natural selection function. In Clifford's evolutionary view, "It is necessary to the tribe that the pious grapheme should be encouraged and preserved, the impious character discouraged and removed" ("On the Scientific Basis of Morals" 294). Thus, his theory of the evolution of ethics argues that natural selection in human being societies might operate at the level of the grouping rather than the individual, favoring the "pious graphic symbol" over the "impious," the latter identified by his failure to adhere to the dictates of his "tribal self." Among other things, this potent claim clearly implies that ethics is a legitimate object of scientific study.

Academy College London, translated the work of the not-Euclidean geometer Riemann, and predictable Einstein's theory attributing the force of "gravity" to an effect of curved infinite rather than the activity of a mysterious strength, William Kingdon Clifford (1845-1879, Fig. 1) was both the youngest member of the "Metaphysicals" when he joined and, eventually, one of the well-nigh provocative spokesmen for the "agnostic" side in the Social club's debates. Clifford was proposed for membership by T. H. Huxley in 1874 shortly after he became Professor of Mathematics at University College London while still in his twenties and he delivered his beginning paper to the group, "On the Nature of Things in Themselves," on the ninth of June, 1874. A strident agnostic, both celebrated and reviled during his brusque life for attempting to ground ideals in the very earthly "conscience of the tribe" rather than orders from heaven, Clifford would draw on the work of Darwin (especially some comments made by Darwin in The Descent of Man [1871]) to redefine the meaning of "piety," associating the term "the pious character" with one who remains faithful to the dictates of the "tribal self," an introjected moral authority whose dictates serve a natural selection function. In Clifford's evolutionary view, "It is necessary to the tribe that the pious grapheme should be encouraged and preserved, the impious character discouraged and removed" ("On the Scientific Basis of Morals" 294). Thus, his theory of the evolution of ethics argues that natural selection in human being societies might operate at the level of the grouping rather than the individual, favoring the "pious graphic symbol" over the "impious," the latter identified by his failure to adhere to the dictates of his "tribal self." Among other things, this potent claim clearly implies that ethics is a legitimate object of scientific study.

By deriving ethics from evolution and attempting to shift the focus of scientific interest from the "private" to the "group," Clifford eventually became an effective polemical vocalism on the "godless" side of the acerbic debates over design and natural pick that characterized British intellectual life more than broadly in the menstruation. Moreover, the work he did in his short lifetime (and the piece of work published later on his decease by the defenders of his reputation such as Karl Pearson and his wife, the novelist Lucy Clifford) ensured a central office for his ideas in the increasingly heated debates almost the nature of the "social" in what would eventually exist chosen "Social Darwinism." In fact, his categorical dismissal of "self-regarding virtues" ("there are no cocky-regarding virtues") made him an constructive critic of Utilitarianism as well—indeed, of all ethical systems which have the individual as a starting point ("Scientific Basis" 121).

Although he was the youngest member of the Metaphysical Society and was non invited to bring together the grouping until it had been in existence for five years, he seems to accept apace become i of the almost controversial, if not influential, members of that distinguished, and varied, group. His importance clearly stemmed in function, non only from his challenging philosophical claims about the origins of human ethical reasoning, but also from the clarity with which he presented these ideas in his lectures and essays. Indeed, "The Ethics of Belief," which was presented to the Social club in 1876 and published in a different grade in the Contemporary Review in 1877, stirred up a meaning controversy, cartoon sharp criticism from Matthew Arnold amongst others and ultimately helping to spawn William James'southward thoughtfully critical response twenty years later in "Volition to Believe." Clifford's very attainable prose mode contributed mightily to stoking the controversy over "The Ethics of Belief," for in that essay Clifford non only avoided the obscure jargon that is sometimes a distinguishing feature of metaphysical debates, but illustrated his claims with familiar examples that his audience establish variously compelling or infuriating. If not the nigh complex argument, "The Ethics of Belief" is, however, the most important and provocative polemical piece of work produced past any of the grouping of "Metaphysicals" that Bernard Lightman calls "the agnostics" (Huxley, Tyndall, Stephen, and Clifford [Lightman 2]). Indeed, one might say that Clifford takes the fear that many believers harbored—the fear that to challenge Christian metaphysics is to undermine Christian ethics—and turns it against the prejudices of the devout by accusing them of immorality precisely for promoting belief in metaphysical entities for which in that location is no compelling evidence.

"The Ethics of Belief" begins with the claim that it is immoral to believe annihilation on bereft evidence. 1 case Clifford gives involves a shipowner who decides to allow a vessel to exit port despite his knowing that the prove points to its existence unseaworthy. Whether he believes the ship to be seaworthy (and believes this sincerely) or whether the ship actually does sail successfully to its adjacent port of call (and thus avoids disastrous consequences), is irrelevant. The shipowner is still acting in an "immoral" way in allowing the send to set sail whether it reaches its adjacent port or not, because he is acting against what the preponderance of the evidence tells him about the send's status ("Ethics" 70). Ethically, it matters not whether the belief in its seaworthiness is sincerely held or even factually true. What matters is that the shipowner in this case ignores what the evidence points to, his belief is held on insufficient evidence, and thus, he acts in an immoral manner. Moreover, in Clifford's view, "no man'southward belief is…a private matter which concerns himself alone" ("Ethics" 73). All beliefs have serious ethical consequences for others. To acquit in a credulous way is not only to brand an error of reasoning relevant just to 1'due south ain private state of mind; rather, to fall into credulity is to perform an immoral deed with serious consequences for other people. As Clifford says,

The danger to social club is not but that information technology should believe incorrect things, though that is great enough; but that it should become credulous, and lose the habit of testing things and inquiring into them; for then it must sink dorsum into savagery. ("Ideals" 76)

If one takes a unlike example, for instance, a seemingly harmless belief in spirit mediums, one can run into why Clifford refuses to concede that even such ostensibly harmless beliefs are actually harmless to society. Considering these beliefs can only be sustained by ingrained habits of refusing the conclusions entailed by testify, to believe in spirit mediums is to foster credulity more than generally and thus to encourage habits of refusing to inquire into the evidence for belief. It is no surprise, then, to learn that Clifford was at odds with such Metaphysicals equally Henry Sidgwick and Arthur Balfour on this issue, or to acquire that he in one case successfully exposed the "famous Williams" equally a fraud at ane of his séances (Madigan 34).

Clifford's claims in "The Ethics of Conventionalities" excited vituperative criticism from a variety of Metaphysicals and others. The offset response to announced in impress came from Henry Wace in The Contemporary Review in June 1877. Another of Clifford'southward critics, William George Ward, the Roman Catholic editor of the Dublin Review, followed with perhaps the harshest polemical attack on Clifford in an article entitled "The Reasonable Ground of Certitude," which appeared in Nineteenth Century in 1878. A deft practitioner of hyperbolic argument himself, Ward zeroed in on the hyperbolic chemical element of Clifford'due south argument: his claim that i has an upstanding obligation to examine the evidence for all behavior. The counter instance Ward gives—of a human being in a hamlet who bases his conviction of the superiority of his village's cricket xi to the cricket eleven of a neighboring village on no evidence any–is an agreeable reductio advertizing absurdum of Clifford's claim about the immorality involved in believing anything on insufficient testify (Madigan 87-eight). Clifford's claims could exist caricatured in such a way by anyone who notices that, in fact, all of united states do operate on many beliefs day-to-day that we have neither the patience nor the time to examine the evidence for. Even so, Ward'due south set on on Clifford ends with Ward elaborating a sophistical argument in defense of the Catholic Church'southward refusal to let its faithful to read the works of skeptical authors like Clifford (Qtd in Madigan 89). This is precisely the attitude to belief that Clifford is criticizing in his essay and his most vituperative critic among the Metaphysicals cannot avoid exposing, in his own essay attacking Clifford's position, exactly the anti-rational opinion Clifford and then deftly skewers in his own.

The Metaphysical Order was organized not only to provide a forum for debating metaphysical and epistemological claims. All its members—whether agnostic or not—appear to accept shared the fear that serious upstanding bug were at pale in these metaphysical debates. In short, the Lodge implicitly sought to address what might be called Dostoyevsky's question: if God is dead, is everything permitted? Clifford, thus, was, if anything, equally interested in addressing the question of the origins of morality as in raising doubts about the existence and wisdom of God, and part of what made "The Ethics of Conventionalities" so controversial was Clifford's aiming a direct set on in it on the morality of metaphysical commitments. To believe in angels is not simply wrong-headed to Clifford; information technology is morally wrong.

Clifford's earlier essay "On the Scientific Basis of Morals" is peradventure his most complex and novel handling of the evolutionary foundation for morality (information technology was start published in The Contemporary Review in 1875). Not quite as provokingly polemical, perhaps, as the subsequently "Ethics of Conventionalities," this essay is, nonetheless, the most complete statement of Clifford'south views on what he chosen "the tribal self"—an ethical agency produced by evolution but i that is not identifiable with any organized faith. He begins past arguing that all humans have been blessed by evolution with a "moral sense," which he argues inspires feelings of "pleasure or unpleasure" in the doing of deportment and which is "felt past the human being mind in contemplating certain courses of acquit" (287). This does not at all advise to Clifford, however, that moral judgments are as individual as humans are. The "maxims of absolute or universal correct" are not necessarily "universal" only they are felt to be independent of the individual: their ability to compel human behavior comes partly from the fact that they embody the moral authorization of the grouping rather than just the individual (288). The source of moral agency is ultimately this "tribal self," a component of the human mind that shapes human being moral beliefs in ways that take worked to the benefit of the tribe over the course of evolutionary time. Our "vicious" ancestors followed the dictates of this agency, and this accounts for why "the savage is not only hurt when everyone treads on his foot only when anybody treads on his tribe" (291). Emphasizing Darwin's insight (in The Descent of Human being) that the ability of humans to cooperate through language means that, in human evolutionary history, natural selection might well have operated as much to the benefit of the social group as to the benefit of the individual, Clifford argues, "natural selection will in the long run preserve those tribes which have approved the right things; namely those things which at that time gave the tribe an advantage in the struggle for beingness" (292-three). Hence, what we phone call "censor" is no more than than "self-judgment in the name of the tribe" (293). To trace the foundations of ethical judgment, we demand not travel to ![]() Sinai. We need merely examine the evolutionary function of morality: "Those tribes have on the whole survived in which conscience approved such deportment as tended to the improvement of men's characters as citizens and therefore to the survival of the tribe" (297).

Sinai. We need merely examine the evolutionary function of morality: "Those tribes have on the whole survived in which conscience approved such deportment as tended to the improvement of men's characters as citizens and therefore to the survival of the tribe" (297).

The evolutionary model of morality that Clifford develops here necessarily commits him to something he delighted in—redefining religious linguistic communication for polemical purposes, in this instance, to ground ethics in the material foundation of evolutionary history, to accept it out of the possessive easily of the religious who insist on grounding morality in the orders of a deity. Thus, "piety" no longer is to be seen as a behavioral response to the demands of ane's immaterial God, its proper form shaped by the dictates of religious authority, but rather as a behavioral response to what is demanded by "the tribe," a response conditioned by evolutionary advantage:

It is necessary to the tribe that the pious graphic symbol should be encouraged and preserved, the impious character discouraged and removed….[T]he actions whose open up approval is liked past the tribal cocky are called right deportment, and those whose open disapproval is disliked are called wrong deportment. (294)

Clifford was ahead of his time in helping to define the emerging late Victorian evolutionary concept of "social efficiency" although he deploys the concept in a more sophisticated way than would later exist done by Benjamin Kidd in his Social Evolution of 1894, a work which popularized the term and which fabricated a name for its heretofore unknown author partly because in information technology he assigned to organized faith the evolutionary function of promoting social cohesion. Since the "tribal self" is responsible for promoting "pious" beliefs, and since Clifford's notion of "pious" behavior redefines virtue every bit what serves the goal of evolutionary efficiency for the group, we tin and so manipulate with the unnecessary hypothesis of God, not to mention the demand for assigning a grandiose social role to organized forms of religion. Moreover, there can be no "self-regarding virtues," according to Clifford, no upstanding requirements favoring the do of virtues such as prudence and temperance which take no clear begetting on the welfare of others. All virtues tin can only "be rightly encouraged in so far as they are shown to conduce to the efficiency of a denizen; that is, in then far as they finish to be self-regarding" (298). Moreover, virtue cannot be grounded in the practice of altruism, which Darwin ruled out as an incommunicable outcome of the operation of natural selection. Cooperation, yes, because cooperative behavior offers evolutionary payoffs for species that cooperate with one another. Altruism, no, because, as Clifford says, "Piety is non Altruism. It is not the doing good to others as others, just the service of the community by a member of information technology, who loses in that service the consciousness that he is anything different from the community" (299). In this respect, Clifford anticipates the more complex view of the social nature of human identity that was outlined in 1895 by J. A. Hobson in his trenchant critique of Kidd'due south Social Evolution (Hobson 302-3).

In another of his essays, "The Ethics of Organized religion," Clifford offers a direct challenge to the claim that organized religion serves social efficiency (it showtime appeared in print in the Fortnightly Review, July 1877). Clifford'southward example against religion is based partly in a critique of metaphysics and partly in a view that religions persistently confound "purely ceremonial" proscriptions with necessary moral laws ("Organized religion" 365). Insofar equally they produce and reproduce this confusion, they work confronting social efficiency. Thus, he cites two famous comments attributed by the New Testament to Jesus: "He that believeth not shall be damned" (King James Bible: Mark xvi:16) and "Blessed are they that have not seen and yet have believed" (Male monarch James Bible: John 20:29). Clifford'southward response to these claims is, "For a homo who clearly felt and recognised the duty of intellectual honesty, of carefully testing every belief before he received it, and particularly before he recommended it to others, it would exist impossible to accredit the profoundly immoral teaching of these texts to a true prophet or worthy leader of humanity" ("Faith" 102). If believing on insufficient evidence is "immoral," information technology necessarily follows that the founder of Christianity, at least in this aspect of his teaching, is a greatly immoral person.

Clifford's influence among the devout would ultimately exist limited by this tendency to defiant polemics, and there is little bear witness in any case that the more conventionally religious members of the Metaphysical Society had the slightest interest in being persuaded to share his views. While his ideas stirred up passionate back up among the "agnostic" group in the Metaphysical Club, fifty-fifty the agnostics hesitated, after his death, to promote his ideas too publicly out of the fear that they would endanger their ain, hard won, professional respectability. The publication of Clifford'southward "Ethics of Conventionalities" in the Contemporary Review in 1877 not only seems to have led to the sacking of its editor, James Knowles, by the new owners of the journal, but information technology ensured that Clifford himself "became an object of persistent vilification in the new more than doctrinally conservative Contemporary that began to announced afterward" (Dawson 168). Even before he had been asked to join the Metaphysical Society, Clifford'south views on sexuality and divorce and his commemoration of Swinburne and Whitman every bit the exponents of "cosmic emotion" in a May 1873 Sunday Lecture Series address had raised eyebrows amid his "agnostic" friends (Dawson 169; "Cosmic Emotion" 411-29). According to Dawson, afterwards Clifford's death in 1879, T. H. Huxley set out deliberately to do what he could to protect Clifford's reputation from existence sullied by association with "political radicalism, extremist atheism, and Swinburne's controversial aesthetic poetry"–all of which were nonetheless important to Clifford in his lifetime (Dawson 165). Clifford's ideas about divorce were quite radical for their time, and his critique of metaphysics positioned him as the almost strident of the "agnostics." Moreover, his celebration of Proudhon and Swinburne tied him closely both to utopian socialism and aestheticist verse in the minds of his critics (165). Clifford's shut friends and colleagues, Frederick Pollock and Leslie Stephen, who posthumously edited and published his Lectures and Essays, were plainly and then worried about protecting his reputation after his decease in 1879 that they bowdlerized a number of the essays in society to leave a better "impression" with readers (173). While the young Karl Pearson, who edited Clifford's posthumously published The Common Sense of the Exact Sciences (1885), happily used material from Clifford'southward provocative essay "Mistress or Wife" in his essay "Socialism and Sex activity," Clifford's wife Lucy "subtly refashioned aspects of Clifford's actual personality that might now play into the hands of his numerous adversaries" [after his decease] (187). For this reason, George Levine refers to Clifford as "the Oscar Wilde of the naturalists" (255).

Withal controversial Clifford'southward views on sexuality, aesthetic poetry, and divorce ultimately fabricated him, his polemical essays on ethics for the Metaphysical Society ought to be considered a major contribution to the study of the evolutionary origins of ethics. Moreover, he was certainly more responsible than whatsoever of the "Metaphysicals" for placing ideals squarely in the domain of science. His writings and lectures on this topic are characterized past directness, a carefully logical form of argumentation, and a resort to Scriptural examples that infuriated his opponents and left his supporters cheering him. The tone of his essays, however, is possibly non quite equally clear every bit one would think. Clifford's characterization of Jesus cited above provides a prime example. Does he truly believe that the Jesus who commends blind organized religion is an immoral person or is he deliberately employing a hyperbolic rhetorical strategy here designed to produce maximum stupor? While there is no particular reason to doubt the sincerity of his claims, the question of tone–and thus, sincerity–has to be raised just because it could not have escaped his attention that he was firing a Large Bertha at the defenders of Christianity. Bernard Lightman has argued that Victorian faithlessness was anything but atheistical. That is, the agnostic group shared with many traditional theists in the Victorian Age the belief that metaphysical debates, in the last analysis, eddy down to discussions about the limitations faced by the human being mind in trying to comprehend an ultimately unknowable God. Thus, the agnostics were not attempting to destroy religion. Instead, they sought to purify it (Lightman 125). Moreover, Lightman argues that Clifford retained "a high regard for the original spirit of Christianity" despite being the most "fell" of the agnostics in his attacks on information technology (122). If Lightman's claim is accurate, Clifford perhaps must be seen less equally a consistent intellectual radical and more as a figure of multiple contradictions: a scientific materialist imbued with "cosmic emotion"; an empiricist unable to forsake things in themselves; the most "savage" critic of organized Christianity and Christian metaphysics in the catamenia who nevertheless retains a great fondness for the moral example of Jesus Christ; an ethicist who derives ethics from evolution just who cannot finally give up higher–if not high-minded—aspirations for human society.

published January 2013

HOW TO CITE THIS Co-operative ENTRY (MLA format)

Bivona, Daniel. "On W. Grand. Clifford and 'The Ethics of Conventionalities,' 11 Apr 1876."Branch: Great britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Internet. Web. [Here, add your concluding date of admission to Co-operative].

WORKS CITED

Berman, David. A History of Atheism in Britain: From Hobbes to Russell. London, New York and Sydney: Croom Captain, 1988. Print.

Clifford, William Kingdon. The Common Sense of the Exact Sciences. Ed. Karl Pearson. London: Kegan Paul Trench Trübner and Co., 1907 [1885]. Web. 16 Oct 2012.

—. "Cosmic Emotion." The Nineteenth Century ii (1877): 411-29. Print.

—. "The Ethics of Conventionalities.""The Ideals of Belief" and Other Essays. Ed. Timothy J. Madigan. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 1999. 70-96. Print.

—. "The Ethics of Religion.""The Ethics of Belief" and Other Essays. Ed. Timothy J. Madigan. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 1999. 97-121. Print.

—. "On the Scientific Basis of Morals." Lectures and Essays by the Late William Kingdon Clifford. Eds. Frederick Pollock and Leslie Stephen. second ed. New York: Macmillan and Co., 1886. 287-99. Web. one March 2012.

Darwin, Charles.The Descent of Homo and Selection in Relation to Sex. London: John Murray, 1875. Print.

Dawson, Gowan. Darwin, Literature, and Victorian Respectability. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge Upward, 2007. Impress.

Hobson, J. A. "Mr. Kidd's Social Evolution." American Periodical of Sociology 1.3 (Nov.

1895): 299-312. JSTOR. 14 March 2012.

James, William. The Will to Believe and Other Essays in Popular Philosophy. New York, London, Mumbai, Calcutta, and Madras: Longmans Light-green and Co., 1896. Web. xxx June 2012.

The Holy Bible. Authorized King James Version. New York and Scarborough, Ontario: Meridian Books, n.d. Impress.

Kidd, Benjamin.Social Evolution. New York: Macmillan, 1894. Print.

Levine, George. "Scientific Discourse every bit an Alternative to Religion."Victorian Religion in Crisis: Essays on Continuity and Alter in Nineteenth Century Religious Conventionalities. Eds. Richard J. Helmstadter and Bernard Lightman. London: Macmillan, 1990. 225-61. Print.

Lightman, Bernard.The Origins of Agnosticism. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins Upward, 1987. Print.

Madigan, Timothy J. West. G. Clifford and "The Ethics of Belief." Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009. Impress.

Metcalf, Priscilla.James Knowles: Victorian Editor and Architect. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1980.

Papers Read at the Meetings of the Metaphysical Lodge (1869 to 1880). London: Metaphysical Society, n.d. Web. 1 June 2012.

Wace, Henry. "'The Ethics of Belief': A Respond to Professor Clifford."Contemporary Review 30 (June 1877): 42-54. Print.

Ward, William George. "The Reasonable Footing of Finality."The Twentieth Century

(formerly Nineteenth Century) 3 (1878): 531>-<547. Web. 5 July 2012.

RELATED Branch ARTICLES

Ian Duncan, "On Charles Darwin and the Voyage of the Beagle"

Martin Meisel, "On the Age of the Universe"

Cannon Schmitt, "On the Publication of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of the Species, 1859″

stephensondoorcall.blogspot.com

Source: https://branchcollective.org/?ps_articles=daniel-bivona-on-w-k-clifford-and-the-ethics-of-belief-11-april-1876